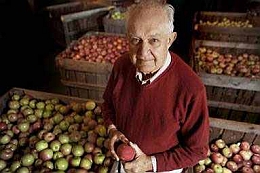

I recently sat down with Tom Burford at his home in Lynchburg, Virginia to talk about apples, cider, agrarian values, and much more. During the course of our conversation, Tom mentioned a YouTube video in which he speaks candidly on matters dear to him, including the reasons why he believes cider virtually disappeared from American commerce after World War II. The clip is criminally underwatched—only 328 views as I write this—so please enjoy it and share it with friends!

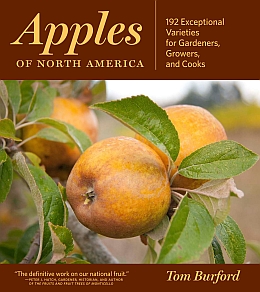

Tom will soon embark on a 20+ city book tour in support of his soon-to-be-released Apples of North America: 192 Exceptional Varieties for Gardeners, Growers, and Cooks. I encourage you to pre-order a copy—or even better, attend one of his book signing events and support the bookstores where he is appearing. Tom has devoted the latter part of his life to educating the public about apples and cider; he is truly a national treasure that you won’t want to miss hearing in person.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPq3-CB-JmM&start=74&end=966&rel=0]

[Tom makes a brief appearance at the very beginning of the video, but I have only transcribed the segment that begins at 1:14 and ends at 16:06. This footage was shot at the 2010 Heritage Harvest Festival; this year’s event will be held September 6-7 and Tom is co-presenting a workshop on pairing apples with cheese on Saturday the 7th.]

Here we are at Monticello for the 4th event, since the last year at Montalto. I just finished doing a cider workshop in the Virginia tradition. It would be the same type of cidermaking I talked about that Jefferson would have done here at Monticello. And that would have been stored in the cellar which has recently been redone in the house. If you have an opportunity, go by Monticello and take a look at the new wine cellar and the cider storage.

I went through pressing of the Virginia Hewes Crab, which comprised the North Orchard here at Monticello. And Jefferson preferred the cider made from this. He had a cidermaker named Jupiter Evans, who was born the same year as Jefferson, and who became his friend and cidermaker. After Jupiter died here at Monticello, his granddaughter wrote him at the White House, where he was serving as President, that the apprentice was making the cider but there had been explosions in the cellar at night. So apparently the apprentice wasn’t paying very close attention to Jupiter! But we were pressing the Virginia Hewes Crab, one of the great cider makers actually of the world. As a single variety, the audience when they sampled it, they were very impressed. It at least showed the audience that cidermaking is possible at home, and you can use the right apple and have some exquisite juice.

Cider sort of disappeared from commerce—good cider disappeared from commerce—because after the Second World War, when there was a surplus of the Red Delicious apple, most of the cider that was sold on roadside stands were made of Red Delicious apples. Which is undoubtedly the worst variety you could use for making cider! So at about that same time there was motoring. In the late ’40s and early ’50s, here in this area, parents would take the kiddies up on the Blue Ridge Parkway. In the fall there were the fruit stands. And they would say, “Let’s stop and get some apples and cider to drink.” So they passed cups of this Red Delicious cider back to the kids, and they would take a sip, and would think—and often would be very vocal about it—“This is undoubtedly the worst cider I have ever put in my mouth. I hate cider, I will never drink it again.” So we lost a whole generation of consumers who demanded a good product.

This has all changed now, and this is one of the hot new things that’s happening. Cidermaking—both fresh ciders with the right apple varieties as well as hard cider—is being made by cideries that are springing up all over the country. Here in Virginia there are two major cideries: Vintage Virginia Apples which is eight miles south of the city of Charlottesville, and Foggy Ridge Cider which is over near Floyd, Virginia in Southwest Virginia. They are undoubtedly doing something right because the supply will not fill the demand. So every year they are trying to make more and more. More and more people are discovering cider, and I am doing my best to educate the public that cidermaking is something that you can do at home. Or if not, it will become available to buy.

Vintage Virginia Apples is the parent of the Albemarle CiderWorks. And it is expanding very fast, and they are beginning to put their ciders into the markets. Not only in Central Virginia, but outside of Central Virginia. There is apparently a great demand for them, because they have recently put two more 1,500-gallon fermentation tanks into their cidery, so that speaks for itself. The spinoff and the great thing for the orchards is that many of the varieties that are used [for cider] can come from the orchards who have been trying to export or sell [apples] otherwise. So we can make a whole new cottage industry with cidermaking and [small-scale] cider, cider can once again become a drink of choice.

Sort of imagine that with all of the soft drinks in one day that are consumed, if all of that were cider, we would not only be healthier, but economically it would spawn many more orchards being planted with good making cider varieties. Not only should you find apples locally for fresh eating, but please buy cider locally. For goodness sakes, don’t go into the supermarket and buy the cider that they have, because they are made of concentrate that comes out—not from this country, I will say—we know who the great suppliers are offshore. It’s bilious. And if we continue to buy and use that and try to feed it to the future generations of cider drinkers, we are going to repeat exactly what happened before. They will find it bilious, they will find it disgusting, and they’ll say “I hate cider and I’m not going to drink cider.” So we need to provide good, locally-made juice—whether it be fresh, or whether it be fermented into hard cider. So this will not only stimulate the local economy, but if we continue to do this, it becomes a model that has a spinoff. Rather than have big conglomerates that are providing us apple products, we will have in Virginia alone hundreds of small, craft-made ciders from varieties that are particularly good for cider, that people will really enjoy drinking.

Jefferson was a great experimenter. He sort of made the model for many—not only vegetables, but for fruits—and planted in his orchard the great, classic American varieties that mostly came out of the plantings of seeds from these huge cider orchards. The water originally was very brackish, it poisoned many people. So when the Northern Europeans and the British Colonies came in to this area, they brought with them the tradition of cidermaking. So the apple for that purpose was very much sought.

And Jefferson had cider on the table every day, as I did as a boy. The cider pitchers were always full. And often if we had visitors, they would go home with a jug of cider if they did not make cider. So it was considered a great favor to give a neighbor who had not cider, a jug of cider. And they occasionally would bring it back for refill, which was wonderful. It was not thought, well, that person’s greedy. No, that person likes cider, likes my cider, and I’m honored.

So Jefferson with his hospitality was much the same way. I’m sure that many of his—particularly European visitors—they discovered American cider. And that it’s distinctive and that it was made with American varieties. The Roxbury Russet, the Virginia Hewes Crab: these were exquisite cider makers that made a vintage cider. That means alone, it made a good cider. Most ciders are a blend. To make a good cider—as to make a good pie—you need four elements. You need sugar, acid, tannin, and an aromatic. And if you don’t have, say, enough tannin, you blend a variety in that would make it very much desirable.

Even as crude as the operations were, there was a sophistication. The scientific elements of cidermaking were pretty well known, but to make really good cider, there is an art—the art of cidermaking. And it’s often a visceral feeling that, “Ah, this would be much more enhanced if I used a little more tannin.” So you add some tannin. So you’re blending until you get something, that, “This is good, this is what I’d like to sit and drink a full glass of.” We all know tea, and if you leave tea—make it very, very, very strong—you have that tannin taste. That is the element that we’re talking about with tannin. The acid—the general process in making hard cider, is to convert the sugar that is in that apple to alcohol. And it will run its natural course of fermentation.

The regulations now and the law in the Commonwealth of Virginia is that your cider has to be 7% or less alcohol. If it goes over 7%, you have apple wine. So that is the demarcation percentage. Before these regulations, you would really want to get as much alcohol as possible. There are certain varieties of apples that are very high in sugar. One is the Grimes Golden. And I have in the past made a cider that was 11% alcohol, that went close to the wines. So the amount of sugar in it, you allow the apple to reach its height of flavor, and then press it. And then you get the full impact of a good, apple-tasting cider.

For many, many years—I’ve lived three-quarters of a century—and for many, many years, I had an operation of an orchard and a nursery, and all of the spinoffs on fruit, including apples with cidermaking. And I suddenly realized about 10 years ago, that this was not known to but few people. So I shut down my operation to devote the rest of my life to teaching, to education, to sharing my experiences with other people. I like to make the approach from low technology, so that we are not damaging the environment, so that we can make it available to all people, make it democratic. And here at Monticello, I’m sure that Mr. Jefferson would be up in the house applauding that statement. Because he wanted all people to share—not only liberty—but good food. So that’s much what his effort was in his vegetable garden and orchard here, was to demonstrate how to grow. So that is what I’m doing at the present time.

And as I stand here under one of the two native crabapples that existed in America when Jefferson arrived—this is Malus coronaria the other one nearby is Malus angustifolia—and I think that, did Jefferson deliberately plant these two here? Because it’s so significant, that these were the only apples in America, and the rest came [from Europe] and were enhanced and marketed and shared by people like Thomas Jefferson.

I would like to conclude in saying that we will find more often, events like this where you can go and see what people are really doing. Everyone here, believe you me, did not go to a distributor and buy anything that they are selling. They come from the earth here. And this is what makes it so special. And each year—this is the fourth year—and each year, more and more people are attending. And we have gone from two events at Tufton Farm, to last year at Montalto, and today the ultimate event right within sight, right on the grounds at Monticello.